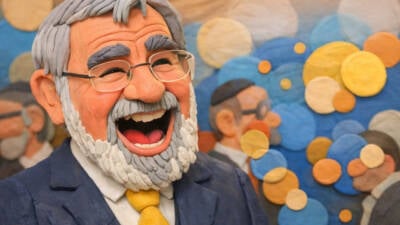

Ceremony & Celebration:

Family Edition

The Ceremony & Celebration: Family Edition resources are designed for kids and students of all ages, to help them discover new insights within the Jewish festivals and to encourage dynamic discussion around your Yom Tov tables.