All Faiths Must Stand Together Against Hatred

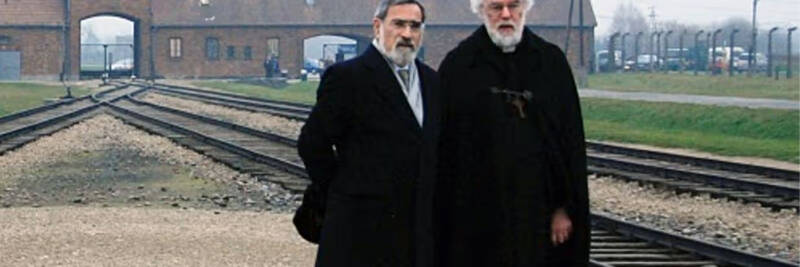

When the Archbishop of Canterbury and I led a mission of leaders of all the faiths in Britain to Auschwitz in November, we did so in the belief that the time has come to strengthen our sense of human solidarity. For the Holocaust was not just a Jewish tragedy but a human one. Nor did it happen in some remote corner of the globe. It happened in the heart of Europe, in the culture that had given the world Goethe and Beethoven, Kant and Hegel. And it can happen again. Not in the same place, not in the same way, but hate still stalks our world.

Nine years ago, when a National Holocaust Memorial Day was first mooted, Tony Blair asked me for my views. I said that I felt the Jewish community did not need such a day. We have our own day, Yom HaShoah, which is, for us, a grief observed. All of us, literally or metaphorically, lost family in the great destruction. All of us are, in some sense, survivors. To be a Jew is to carry the burden of memory without letting it rob us of hope and faith in the possibility of a world at peace.

But such a day might be valuable to all of us, Jew and non-Jew alike, were two conditions satisfied. The first was that, without diminishing the uniqueness of the Holocaust, we might use it to highlight other tragedies: Bosnia, Cambodia, Rwanda and now Darfur. The second was that the day was taken into schools. For it is our children and grandchildren who must carry the fight for tolerance into the future, and we must make sure that they recognise the first steps along the path to Hell.

It was the Holocaust survivors who taught me this. I cannot imagine what they went through. Yet trauma did not turn them inward. They, more than anyone, empathised with victims of subsequent tragedies, and went into schools, teaching children to cherish freedom and be prepared to fight for it. They remain my role models in turning personal pain into sensitivity to the pain of others. About one Holocaust Memorial Day, in 2004, I was initially apprehensive. The organisers rightly chose to focus on the massacre in Rwanda ten years before. How, I wondered, would 80-year-old Central Europeans relate to young survivors from Africa? My concerns turned out to be utterly misplaced. One survivor instinctively recognises another across the barriers of colour, culture, age and creed.

Six months later Mary Kayetesi Blewitt, the remarkable woman who has led the work with the survivors in Rwanda, came round to see me bubbling with excitement. For years, she said, she had been working in obscurity, aided mainly by the Jewish community. Now, because of the prominence given to her work by Holocaust Memorial Day, she had been voted an international woman of the year. The Queen had invited her to Buckingham Palace and the British Government had given a large grant to build Aids clinics in Kigali.

Hence our decision to go to Auschwitz with leading British Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Zoroastrians and Bahai. Grief has the power to unite. Of the 6,000 languages spoken throughout the world today, only one is truly universal: the language of tears. And now, when the tectonic plates on which humanity stands are shifting, leading to violence, conflict and terror throughout the world, we must take a stand against hate – the theme of this year’s commemoration.

Never in my lifetime have we needed that message more. All the danger signs are flashing: financial meltdown, recession and a sense that “things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; mere anarchy is loosed upon the world”. Anti-Semitism is only a small part of the problem. Instantaneous global communication ensures that conflicts anywhere can light fuses everywhere. The internet is the most powerful spreader of hate and paranoia invented.

The world has become more unstable and confusing. At such times people search for certainties. They rally round scapegoats and slogans that simplify. They resolve complex issues into polarities: us and them, the children of light versus the children of darkness, friends and enemies, the saved and the damned. People lose faith in the long, slow process of conflict resolution. They lose the very precondition of justice: the ability to hear both sides. They see themselves as victims and identify someone else to blame.

Academics, who should be guardians of objectivity, become partisan and instigate boycotts. That is what happened in Germany in the 1930s. The greatest philosopher of his time, Martin Heidegger, was a Nazi. Doctors and scientists administered the Final Solution. Carl Schmitt, an anti-Semite, a Nazi, and the leading political thinker of his day, held that liberalism is too weak to sustain passion and conviction at times of crisis. For him, real politics is about identifying an enemy and a cause you are willing to die for. That is how it is in parts of the world today. It must not become the way it is in Britain.

We, the religious leaders and faith communities of Britain, must work hard at our friendship and stand together in this turbulent age. Our visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau was organised by the Holocaust Educational Trust. As we stood together that chill November night, lighting candles and saying prayers where 1.25 million people were gassed, burnt and turned to ash, we knew to the core of our being where hate, unchecked, can lead. We cannot change the past. We can, and must, change the future. For the sake of the victims, for the sake of our children, and for the sake of God, whose image we bear.