The Home We Build Together (animated video)

How can we create a healthy, sustainable society? Does building lead to belonging?

“How do you sustain a cohesive society in the midst of unprecedented religious and ethnic diversity? How, in an age of mass migration, do you integrate minorities without destroying their identity or losing yours? That’s a key issue facing the West today. So let’s look at how societies have dealt with it in the past and where they went wrong.”

Watch Rabbi Sacks’ new whiteboard animation video on ‘The Home We Build Together.’ This video is based on Rabbi Sacks’ book by the same name, ‘The Home We Build Together.’

How do you sustain a cohesive society in the midst of unprecedented religious and ethnic diversity? How, in an age of mass migration, do you integrate minorities without destroying their identity or losing yours? That is a key issue facing the West today. So let’s look at how societies have dealt with it in the past, and where they went wrong.

The first was the way Britain and other European countries did it in the nineteenth century. I call it the country house model. Imagine a hundred immigrants turn up in the English countryside at the gate of an enormous country house.

The owner of the house – an aristocrat – greets the new arrivals with a warm and welcoming smile. “How good to see you,” he says. “There are a hundred of you. I have at least a hundred spare rooms. Please come and stay for as long as you like.” He couldn’t be more hospitable. The only trouble is: he’s the host and you’re just a guest. It’s his home, not yours.

So, in nineteenth century Europe, immigrants found refuge, but they were conscious of being outsiders, guests. That failed – not in England, but in Germany, Austria, France and other European countries who decided, one way or another, that they really didn’t want the Jewish guests any more. That’s how the Holocaust happened with so little protest from the general population.

In America, in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, there was a different model. It was called the melting pot. Into the pot went all the immigrants – Irish, Italian, Jewish – and out came something different. They had all become Americans. At least, that was the theory. What happened, in fact, was that they came out hyphenated Americans. Irish-American, Italian-American, Jewish-American. Many of them, especially African Americans, but others also, felt discriminated against. So, rather than a single national identity you had lots of jangling interest groups. The American motto was E pluribus unum, “Out of the many, one.” But it turned out that there was more pluribus than unum.

So, in the 1970s, Europe and America turned to a new model. The hotel. Imagine a hundred immigrants turn up in a town. The leaders of the town say, “Welcome. Please come and stay in one of our hotels. That’s where we all live. All you have to do is pay the bill, and you’re free to do whatever you like in your room so long as the noise doesn’t disturb the other guests.”

This was the strategy known as multi-culturalism. It was meant to cure the problems of the country house and the melting pot. Now everyone was free to keep their own identities, and they did so, natives and newcomers, on the same terms. All they had to do was pay the bill – taxes – and in return they each had their own room and the hotel services.

The only trouble is that in a hotel, no one belongs. A hotel is not a home. Which upset the people who’d been there a long time and thought they had a home. It was also disastrous for any sense of collective identity. Hotel guests don’t constitute a community. The things that matter, they do in their private rooms. Multiculturalism was supposed to make everyone feel at home but in the end it made no one feel at home. It was supposed to lead to integration, instead it led to segregation.

So, for the twenty first century, we need a new model. I call it “the home we build together.” A hundred immigrants turn up in a town. The leaders of the town say, “Welcome. We’re so sorry we don’t have a country house or a hotel. But we do have some spare land, and lots of building materials, and some expert architects and electricians. So let’s all build you a house together.”

The natives and newcomers work together, side by side, and in the course of building, the newcomers learn the ways of the natives, and the natives benefit from the skills of the newcomers. The newcomers keep many of their old customs, but they also bring their unique gifts as contributions to the town, and they feel they belong because, with the help of the natives, they have built their own homes, which merge architecturally with the other houses in the town.

The model of society as the home we build together emphasizes responsibilities more than rights. It values differences because they’re not used to keep us apart, but rather, they mean we each have something different and special to give to the common good. The town grows, because of all the new food and music and fashions the newcomers bring to the town square. And the natives still feel at home because the newcomers respect their way of doing things. That is integrated diversity.

It’s so much better than the country house, the melting pot and the hotel, because building leads to belonging. When we build, we bond. Society is the home we build together.

SHARE

More from Animations

Time (animated video)

Watch Rabbi Sacks’ view on the Jewish way to understand time.

Israel: Home of Hope (animated video)

Rabbi Sacks on the connection between Ezekiel’s Vision of the Valley of Dry Bones and the creation of the modern State of Israel.

Connecting to God (animated video)

With audio recorded by Rabbi Sacks in 2010, here is a new animated video of the three key ways we can each connect to God.

Being Jewish (animated video)

An animation on understanding our identity and our Jewish heritage.

Morality (animated video)

“We need to restore that sense of collective responsibility…”

The Connection between Judaism and Israel

Rabbi Sacks on 'The Great Partnership'

Do Religion and Science Always Contradict Each Other?

Rabbi Sacks on 'The Politics of Hope'

Can we create a new kind of politics?

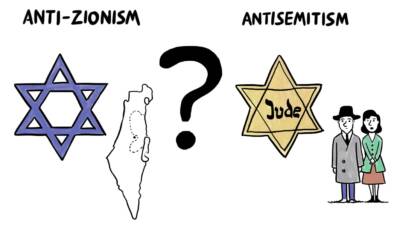

The Mutation of Antisemitism

What is antisemitism, and how has it changed over the centuries?

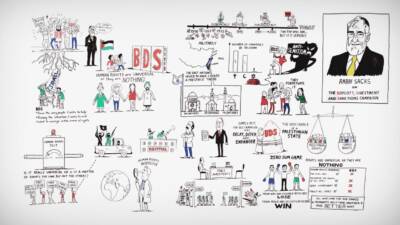

On the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign

Why is it important to understand and oppose the BDS campaign?

Why I am a Jew

An animated video on Jewish identity and finding your Jewish purpose