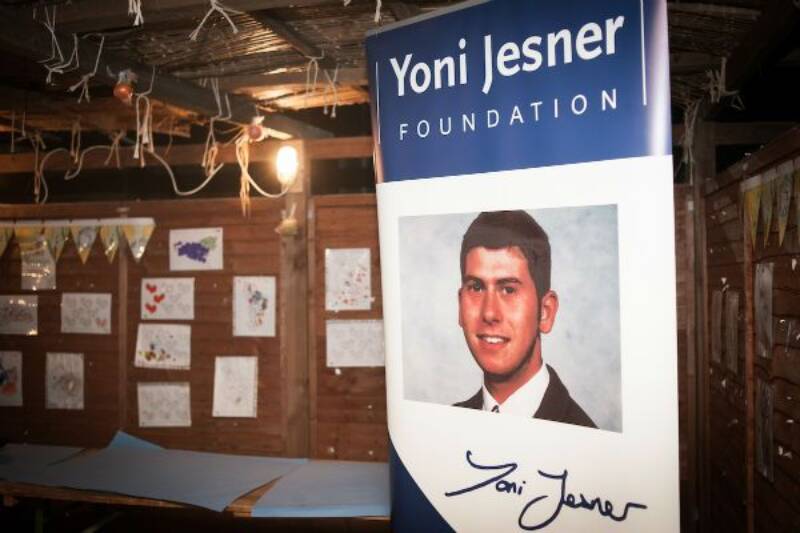

Yoni Jesner, of blessed memory, was a remarkable young man whose death at the hands of a suicide bomber has devastated all who knew him.

I met him in Jerusalem in January at a meeting of British students on a gap year in Israel. It was clear then that he was a natural leader, a young man of spiritual depth and moral principle whose smile and warmth drew others to him and lifted them by his example. Those who knew him loved and admired him. His memory will live on as a testament to the very best in Jewish youth.

These words are my tribute to him and to the youth movement, Bnei Akiva, to which he gave so much.

We observe Succot, says the Torah, “so that your descendants will know that I made the Israelites live in booths when I brought them out of Egypt.” What, though, is special about this fact? Pesach and Shavuot commemorate miracles: the Exodus from Egypt and the Giving of the Torah at Sinai.

What is miraculous about living in booths? On this, the Talmud records two views. According to Rabbi Eliezer, succot represent the “Clouds of Glory” that accompanied the Israelites on their journey. According to Rabbi Akiva, however, succot represent exactly what they are: temporary dwellings, shacks with a canopy of leaves for a roof.

On Rabbi Eliezer’s view, the miracle is self-evident. For 40 years, God’s sheltering Presence protected the Israelites from heat by day, cold by night, and the wild animals and enemies they encountered on the way.

On Rabbi Akiva’s view, though, the succah seems to represent no miracle whatsoever. That the Israelites lived in temporary dwellings for 40 years was only to be expected. That is how nomads live. It is what the Bedouin do to this day.

There is, however, a beautiful explanation: Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Akiva differed not on whether there was a miracle but rather, to whom it belonged. According to Rabbi Eliezer, the miracle was God’s. It was He who protected the people on their long walk to freedom. According to Rabbi Akiva, the miracle was that of the Jewish people.

Though the journey from Egypt to the promised land took forty years, and though the Israelites faced setbacks and digressions, they did not give up or lose faith or despair. According to Rabbi Akiva, while Pesach and Shavuot represent God’s love for the Jewish people, Succot represents the Jewish people’s love for God. Where do we find such an idea?

In the words of Jeremiah we say on Rosh Hashanah. Elsewhere the story of the years in the wilderness is told in terms of the people’s rebelliousness and obstinacy. Jeremiah, though, describes it quite differently.

“I remember the kindness of your youth, the love of your betrothal – that you were willing to follow Me into the desert through an unsown land.”

That was Israel’s greatness. It is easy to worship God when you have safety and security. But Israel came of age as a nation long before it knew such things.

It was born in the desert with no fixed home, vulnerable, exposed, yet willing to follow the call of God. That was the miracle – faith in the midst of uncertainty. What Rabbi Akiva was saying was: Look at the succah and you will see where our people was born.

Our ancestors lived in humble dwellings like these, yet they reached heights of the spirit unattained by those who lived in royal palaces. The succah was the matrix of Jewish courage, the birthplace of a people obstinate in their loyalty to God.

Little can Rabbi Akiva have known how true this idea would prove to be. For almost 2,000 years, dispersed and scattered across the globe, Jews never knew whether the place they were this year would still be their home a year later.

In place after place, they were forced to move by a ruler’s whim or a shift in the prevailing winds of prejudice. They might so easily have given up and abandoned their faith. Some did. Most, however, did not. They were the only minority who consistently refused to capitulate to the dominant faith. Their sheer loyalty amazed and perplexed those who reflected on it.

That is the faith we remember and pay tribute to on Succot – of a people who were sheltered only by the canopy of their trust in God, yet who never lost that trust in the midst of vulnerability. Succot tells us that emunah, faith, is not certainty. It is the courage to live with uncertainty, facing risk unintimidated and danger unafraid.

That is the courage Yoni Jesner showed – and which every Israeli has shown these past two years. They have faced a remorseless campaign of terror, driven by hate, that has cost hundreds of lives and left thousands injured.

There are two kinds of heroism. There is the heroism of rare moments – of battle, crisis and war, when people are inspired to great acts of valour. But there is another kind of heroism, quieter but no less remarkable: the heroism of everyday life when an entire people is exposed to danger, not on the battlefield but in the street or a shop or at a bus stop, when simply staying and being there take courage.

That – according to Rabbi Akiva, the inspiration of Bnei Akiva – is the courage we celebrate on Succot. It is the courage every Israeli has demonstrated in the past two years. It is the courage Yoni Jesner showed.

Its significance is immense. Those who practise terror aim to intimidate and unnerve. If there is one people on the face of the earth who cannot be intimidated it is the people who, year after year, sat in a succah, exposed to the wind, the rain and the cold, and yet called it z’man simchateinu, “the season of our joy”.

That is heroism awesome in its grandeur, and it is the mark of all who live in Israel or spend time there today.

It turned out, though, that Yoni had a last and yet more deeply moving message for us. This week we discovered that his family had donated one of his kidneys to save the life of a seven-year-old Palestinian girl who had been on dialysis for two years waiting for a suitable donor. That is moral greatness of a high order – to create life out of death and turn a potential enemy into a friend.

A people is as great as its ideals, and Yoni lived those ideals to the limit. We will not forget him. We will cherish his memory as a blessing and inspiration.